December 2, 2019

Horses, Houses, and History in Saratoga Springs with Samantha Bosshart

Nestled in the verdant fields and forests of the Hudson Valley, Saratoga Springs is a historic jewel of New York State – a place where the past is evocative and ever-present. The unique and charming character of Saratoga Springs didn’t happen by accident – like many places it’s the result of dedicated preservationists, like today’s guest, Samantha Bosshart who leads the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation. On today’s episode of PreserveCast, we’ll talk about preservation work in a small town with the nation’s oldest sports venue.

Giddy up! We’re talking horses, houses and history on this week’s PreserveCast.

Samantha Bosshart joined the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation in 2008 and under her leadership, the Foundation completed a $750,000 restoration of the Spirit of Life and Spencer Trask Memorial; undertook a comprehensive cultural resource inventory of the Saratoga Race Course and successfully advocated for the Foundation to review capital improvement projects to ensure the preservation of the historic character of the oldest sports venue in the country.

Prior to leading the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation, she held positions at the Historic Albany Foundation and Galveston Historical Foundation. Samantha is a graduate of both Indiana University and Cornell University where she received her Masters of Arts in Historic Preservation Planning.

[music] From Preservation Maryland Studios in the historic podcast district of Baltimore, this is PreserveCast.

Nestled in the verdant fields and forests of the Hudson Valley, Saratoga Springs is a historic jewel of New York State, a place where the past is evocative and ever-present. The unique and charming character of Saratoga Springs didn’t happen by accident. Like many places, it’s the result of dedicated preservationists like today’s guest, Samantha Bosshart, who leads the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation. On today’s episode, we’ll talk about preservation work in a small town with the nation’s oldest sports venue. Giddy up. We’re talking horses, houses, and history on this week’s PreserveCast.

Before we start this week’s episode, I really want to thank you for listening. And I want to ask for your help. PreserveCast is powered by Preservation Maryland, a non-profit organization that depends on member contributions to fund its work. This podcast receives no government support and currently has no major funders support. Its budget is entirely dependent on listener contributions. I’m hoping you’ll consider making a quick gift to help support this podcast, which is bringing important preservation stories to thousands of listeners around the country. Think of us as your preservation Netflix. Any amount helps. And you can make a quick online donation by going to preservecast.org and clicking the Donate Now button in the upper right-hand corner. We greatly appreciate it. Now let’s get preserving.

Samantha Bosshart joined the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation in 2008. And under her leadership, the Foundation completed a $750,000 restoration of the Spirit of Life & Spencer Trask Memorial, undertook a comprehensive cultural research inventory of the Saratoga Race Course, and successfully advocated for the Foundation to review capital improvement projects to ensure the preservation of the historic character of the oldest sports venue in the country. Prior to leading the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation, she held positions at the Historic Albany Foundation and Galveston Historical Foundation. Samantha attended both Indiana University and Cornell University where she studied historic preservation planning.

Samantha, it is a pleasure to have you with us here today in PreserveCast to talk all things Saratoga Springs and how you do your work up there in the beautiful Hudson Valley.

Thank you. Well, I appreciate you having me today.

So tell us a little bit about your path to this career. Obviously, you’ve worked for some pretty great preservation groups, Galveston being really a large local preservation group. And now, you’ve led your own preservation organization since 2008, what spurred this interest in historic preservation? How did you end up where you’re at today?

I think, probably for most preservationists, it’s sort of a circuitous route. I grew up with parents that took me to numerous historic sites, collected antiques. I saw my fair share of house museums over the years as a child, but. And I didn’t know that historic preservation was a career. I went to Indiana University in theory to be a business major. That did not work out for me very well [laughter]. And I found that I was drawn to taking history courses. And that is what I ended up getting a major in. However, I didn’t really not to, per se, teach it. And I didn’t know quite what to do once I graduated. And at that time, my parents purchased a property that was adjacent to a historic property that they owned in Galveston that needed extensive rehab, and my dad jokingly said at the time, “Well you could go to Galveston and fix up the houses.” And lo and behold, that is how I ended up in Galveston, Texas. They were three small cottages on one lot and they were located in the East End Historic District, which is actually a national historic landmark. So I undertook a rehab of those buildings, sort of by chance, but having to learn about historic districts, historic guidelines, and how to go about that kind of a project. Once that was completed, I sort of fell into a position at the Galveston Historical Foundation as their preservation resource manager, in which case that’s really where I figured out that preservation was a career and it was something that I had a passion for.

And how long did you stick around there?

I worked for the Galveston Historical Foundation for five years. I did demonstration classes, I did survey work, I helped people research their homes. It was a fun time. It was the anniversary of the Great Storm, we had a special plaque program to recognize houses that had survived that major hurricane. So it was just a fun opportunity to be at such a large preservation organization that is so well nationally recognized. I was so fortunate.

So now you are in a place very different than Galveston. Perhaps there’s some similarities that you could tell us about, but far southern Texas is a little different than the Hudson Valley. And tell us about Saratoga Springs and then perhaps the foundation. Paint us a little picture. What’s it like?

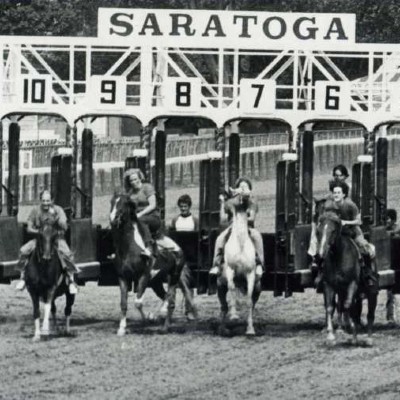

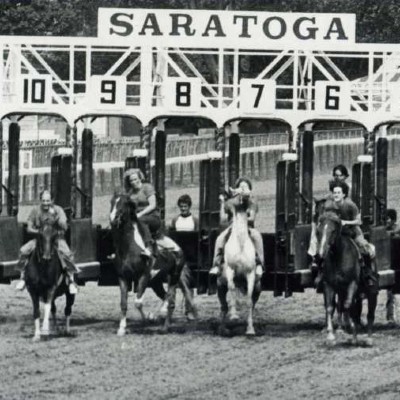

So it’s interesting. You wouldn’t really think that Galveston and Saratoga Springs have much in common, but actually they really do. Galveston was a wealthy resort destination as well as a port. So Saratoga was also a wealthy resort destination and sort of have had similar histories where the wealthy came, beautiful buildings were built, largely during the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Both of them saw an economic decline towards, I’d say, the ’50s and ’60s. Both of them had also a gambling history. So there was that similar Gambling Bob affiliation [laughter], and then they both also had The Strand in Galveston and Broadway here in Saratoga Springs sort of had vacant storefronts and vacant upper floors and saw a real economic decline. And both of them, thanks to local community leaders, decided to invest in their downtowns and one of the tools in that toolbox that helped to bring back those downtowns were preservation. So it seems like there wouldn’t be that much commonality, but there really is, which kind of makes it fun for me, Saratoga Springs was developed by Gideon Putnam in the early 1800s. He built the first lodging tavern, the end, people refer to it as Putnam folly because they didn’t think anybody would want to be in the wilderness in upstate New York, however, that he proved everybody wrong. And at one point in time, Saratoga had one of the largest hotels in the world, the grand union hotel that could accommodate up to 2000 guests, and that was just one of the large hotels that we had here. People came here for the spring waters. The Indians were the first to come to Saratoga and take the spring waters. George Washington did as well. And then we had the Saratoga Racecourse be an important destination. Starting well, technically in 1847, was the first racetrack but thoroughbred racing started to take place in 1863.

So the Saratoga Preservation Foundation should, Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation, obviously is a local preservation group. But what’s a normal day for you like what kind of work do you actually do? Because a lot of preservation groups out there all of them work in different ways. How is it that you organize your work?

Well, I’d say somewhat traditional, we do a little bit of everything, advocacy, education, restoration, and technical assistance. No day is ever in the same. We offer tours. We often provide advisory opinions on best preservation practices to our land use boards. We work with the city of Saratoga Springs on how to promote and continue to preserve our community. We are often partners with them. And we provide technical assistance to building owners as well as we undertake restoration projects. Most recently we helped the First Baptist Church, which actually is the oldest congregation in Saratoga Springs at 225 years old. They have a 1855 Greek Revival church with 19 oh 16 glass windows that were falling into disrepair, their congregation of less than 30 and we helped to raise over $50,000 to help them undertake the first phase of restoring their stained glass windows.

And you do this with it sounds like with that amount of work. This is a staff of 10.

I wish. It is a staff of two full time, myself, and my membership and programs director Nichols. As well as we have a part-time admin and bookkeeper.

So give us an example, you’ve mentioned some of the things that you’ve worked on recently. What are some projects that you’re spending time on right now?

We are working with the city to pass a stronger vacant building registry ordinance that actually incorporates language that’s specific to vacant buildings and historic districts that will be going to a vote soon before the city council.

And if I can ask, what is it because I think a lot of people grapple with that issue. What is it that you’re trying to propose? What’s the legislation actually do?

Currently, the ordinance isn’t as clear as it should be on the expectations of what a owner of a vacant buildings should be doing and that they are to provide a plan to have the building become re-occupied. And this ordinance really sort of strengthens that language. But, in addition, helps to outline some parameters for buildings that are located in a historic district, or that are determined eligible for listing it as a historic building.

So that can make– do you have a significant vacancy problem or is it more speculators? What kind of vacancy issues are you seeing?

We’re very, very fortunate here in Saratoga unlike other cities in the capital region in New York, such as Albany that has anywhere over 900 vacant historic buildings. We only have a handful, but the handful that we do have have been problematic homes or buildings for, I would say– a large number of the buildings on our endangered watchlist have been on that list for nearly 20 years.

So it’s been an issue for a while.

It’s been an issue. And, unfortunately, we haven’t really made much progress. And in fact, over time we’ve lost a handful.

So you’re working on this vacancy issue on the advocacy side. What else is going on with the organization? What are big things that we should be aware of?

One of the other things that what ties into that is we’re hoping to release a most-wanted list about the buildings that we want to see preserved. So that all ties together with the vacant building [crosstalk] ordinance.

And is that new? A “most-wanted”, I like that.

We used to call our endangered list the 10 to save list. And I think we just felt like we wanted to re-package it or re-brand it. And so what we hoped to have is most-wanted, preserved, and secured, and have sort of like old-timey photos and posters to sort of say, “This is what we want, and that they’re wanted.”

And when is that coming? That sounds pretty cool.

Hopefully, in the next couple months is our plan.

So let’s talk a little bit about the other– I mean, you kind of touched on a little bit with the gambling history there. Horse racing, it’s the other big component of the history of Saratoga Springs and the track and the historic research that’s associated with it. You mentioned earlier that racing sort of started in the 1840’s, and then thoroughbred racing started in 1863. What is the history of the track? What should people know about why it matters, its significance. And then maybe we can talk a little bit about what’s there today, and the preservation status of it.

I think what really is truly, truly special about Saratoga Race Course is that it initially was developed through harness racing and fares. It was illegal to bet on horses, so the way to circumvent that was to have trials on the strength of horses. You know, trials. And they became very popular. And through that, they established the first race course– or original race course in 1847 out on a piece of land that had some original farm buildings. And it continued to be successful. In 1863, John Morrissey had a big personality, was a gambler, politician. And he decided to host the first thoroughbred racing at Saratoga Race Course and it was hugely popular to the point where the following summer they purchased another piece of land and erected a new grandstand. Actually, there wasn’t a grandstand at that first track. People would just sort of congregate on their carriages and in the infield. They built the first wooden grandstand in 1864. And through that, that’s when horse racing really sort of took off for Saratoga. We have the Travers Stakes race, which is the oldest stakes race in the country. Over time, the track has developed, right? Today, it has over 200 historic buildings, and it encompasses 350 acres.

Is anything left from 1863?

There are buildings that date back to 1847.

So the answer is yes.

Absolutely [laughter]. It is remarkably, remarkably intact.

And why is that? I mean, because, obviously, we’re recording this in Baltimore, not far from Pimlico, and there’s scant remains of any of the historic structures associated with Pimlico left. Why did it survive the way it did?

I think it’s probably a multitude of factors. I think they had the land to grow per se. There wasn’t intense development pressure directly around the track. The track is really– it’s in town, but it’s sort of just on the outskirts. I think there’s that. I think that there just wasn’t, also, the money to spend on a wholesale redevelopment. And so we were fortunate. They did that at Belmont and Aqueduct. And I think they, fortunately, ran out of funds to do such a thing here at Saratoga. And they just built an addition to the grandstand. I think the buildings that are here, the stables and the cottages, have served their purpose over the years, and there was no need to do a wholesale teardown.

So are there challenges, though, associated with preserving a working racetrack? I mean, are there pressures to change things so that it works better for modern racing and for modern viewers?

Absolutely. Absolutely.

And what role do you guys have in that?

Absolutely, there are challenges. I think the position that the foundation has taken since we first really became involved with Saratoga Race Course intimately was actually, in 2008, the New York Racing Association was up for a franchise renewal with New York State to oversee the three racecourses, Aqueduct, Belmont, and Saratoga. At that time, that lease agreement could’ve gone to anyone. And there was a real fear in the community that a new operator would want to come in and drastically modernize our venue. Take one look at Churchill Downs and what has happened there. That is something that we did not want to see here in Saratoga. Prior to me joining the foundation, they actively brought together a racecourse coalition and advocated for a new franchise agreement to include an unfunded mandate to have a cultural resource survey completed, that capital improvements made it the track be reviewed by the state historic preservation office, and a local advisory board be formed to provide input on changes at the Saratoga Race Course. I think that was instrumental for Saratoga and for our organization. And that sort of led us to become much more involved, understanding it was an unfunded mandate. We undertook the initiative to raise funding to undertake a cultural resource survey of the front side and the backside, focusing on probably 80% of the track. Not all of it has been documented, but we focused on areas that had the most potential to see redevelopment in some capacity. And we’ve established a really good working relationship with the New York Racing Association, which was awarded the franchise agreement.

When it comes to changes, for example, there was a real desire or they felt need to have air conditioned luxury suites. Prior to this year, those were in temporary tractor trailers and a air-conditioned tent that held events. They felt the need that they needed a air-conditioned facility to host events and to have luxury suites. And so they built, recently, an over 30,000 square foot new building. And we were the organization tasked with providing advisory opinions on that design to ensure that it was in keeping with the historic character of Saratoga Race Course.

And that was a challenging process or actually worked pretty well?

I would say that the process worked well. Like I said, we are fortunate to have a good working relationship with the New York Racing Association. They work with Matt Hurf, a frost turf architects who serves sort of as their preservation consultant and architect. He was not the lead architect on that particular building, but he worked with us. And I think what was built was successful.

So you’ve talked a little bit about some projects that you’re working on, projects you’ve worked on in the past, and we heard that you’ve got this cool, most wanted rebrand of your endangered program on the horizon. But what else is next for the foundation? What are you hoping to tackle? And do you have any sort of big dreams for what’s happening there?

I would like for the foundation to undertake a rehabilitation project of perhaps one of the buildings that is on our most wanted list. I don’t know how feasible that is, but that would be one of my dream projects.

And by that, you mean actually taking title to something and rehabbing yourself and either owning it or selling it and kind of doing historic property redevelopment?

Yes, I don’t think I would want to retain ownership. It would be something where we would get it into a condition that somebody could complete an interior rehab in the way that they would want and sell it.

And is that something that the foundation has done before? Or would that be sort of really a new initiative? Have they done it in their past?

In our over 42 year history, yes, it has been done. It has not been done in a very long time.

Yeah. And I noticed or with that because we’re sort of in the same place and are contemplating now our first acquisition in many, many years. So in addition to property development, I know you’ve also been active in looking at the economic impact not only your work but just the broader value of preservation. Do you want to tell people a little bit about the report that you guys issued recently?

Yes. I’m sure as most preservation organizations across the country have always touted that preservation has economic benefits, but we really wanted something that would give us proof of what the value of preservation means to our community. And so we were fortunate enough through some private funding as well as a certified local government grant to partner with the city of Saratoga Springs to do an economic impact study on preservation. And we were fortunate enough to hire Donovan Rypkema of PlaceEconomics. And he looked back at over 20 years of MLS data to really get into the nitty-gritty of the differences between living in a historic district versus a not historic district. And the results were overwhelmingly that preservation does have an economic benefit with property values being higher, holding their value, increasing their value over time. And also, we learned that that’s where most young firms are located are in historic districts, 46%. And then 31% of all jobs at small firms are also located in historic districts. Not only that, which was also surprising is only 6% of the land area is located in a historic district, but we provide up to 14% of the total assessed value in Saratoga which obviously contributes to our income for the city, the county, as well as our school districts.

Yeah. So I mean, no matter way you slice it, preservation really is a powerful economic force. And we see that over and over again, but it’s always good to see new numbers. If someone wants to read the study, can they find it on your website?

Absolutely.

And what is that website?

Easy to remember. And now, the most difficult question for any preservationist, your favorite historic place or site?

Well, I’ve wrestled with this in the past and I will continue to do so. I’ve been fortunate enough to travel around the world. I probably have a favorite historic site in many different countries. So I will answer with probably my favorite site in Saratoga, and that would probably be the Spirit of Life and Spencer Trask Memorial.

So tell us what that is.

It is a bronze sculpture in Congress Park which is a national historic landmark. It was designed by Daniel Chester French and the architectural surround designed by Henry Bacon of the same fame of both of them who did the Lincoln Memorial. And it was in memorial to Spencer Trask from his wife Katrina after he passed away to honor his efforts to preserve the spring waters of Saratoga. He worked with Senator Brackett to pass the first legislation to ensure that the springs in Saratoga would be preserved. We were involved in a four-year restoration of that memorial. And it just has special meaning.

Yeah, and there’s a great picture of it on your website. And I think actually the profile picture for this episode of PreserveCast is you standing in front of a portion of that. Is that correct?

That is correct.

That is correct. Well, this has been a fantastic conversation. It’s interesting to hear about the good work that’s happening all across the country and the efforts that it takes to keep places like Saratoga Springs and its important racing history and its important commercial and residential structures in good repair. It’s a difficult challenge everywhere and wouldn’t be possible without folks like you out in the field. So thank you so much for joining us today on PreserveCast.

Thank you.

[music] Thanks for listening to PreserveCast. To dig deeper into this episode’s show notes and all previous episodes, visit preservecast.org. You can also find us online at Facebook and Twitter at PreserveCast. This program was supported by The Historic Preservation Education Foundation. PreserveCast is produced by Preservation Maryland in Baltimore City. Thanks again for your support and remember to keep preserving.