March 27, 2017

Civil War Medicine and the Modern Day

Jake Wynn joins Nick this week from the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Learn how the study and practice of medicine from the Civil War period is relevant today, and about how Jake and his colleagues are opening the museum up to new audiences through the use of technology, social media, and a variety of innovative practices. We promise it won’t hurt a bit. Check out this week’s PreserveCast!

Introduction

[Nick Redding] Civil War history is a popular topic, especially in a state with as complex a history in the Civil War as Maryland. Medical advances may not be the first thing that comes to your mind as a lasting impact of the long and bloody conflict. But thanks to our guest Jake Wynn of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, that perception may soon change. Stick around and hear how Jake helps people learn about the other kind of medical history on PreserveCast.

From Preservation Maryland Studios in the historic podcast district of Baltimore, this is PreserveCast.

[Nick Redding] Hi, this is Nick Redding and you’re listening to PreserveCast. Jake Wynn is the program coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog. In his work at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Jake has helped expand museum’s use of online and digital media to enhance the visitor experience. We’re excited to have Jake on today to talk about that work on PreserveCast. Thanks for joining us, Jake. We’re glad to have you remotely from your headquarters in Frederick, Maryland.

[Jake Wynn] Thank you so much for having me. I’m really excited about this.

[NR] Great. So Jake, what got you into this line of work? I mean, when did you catch the bug about history and preservation and the Civil War?

[JW] It really starts out really young for me. I was always interested in history. I heard a lot of it from my family growing up and watched a lot of movies that had some kind of historical elements, watching them with my family, and it stuck with me. And so 19th-century American history really fascinated me…and specifically with the American Civil War, I found a really awesome outlet here in Frederick, Maryland, to explore those stories.

[NR] So how long have you been with the National Museum of Civil War Medicine?

[JW] I’ve worked here for three years, and one of those years has been– just over one year– has been full-time here at the museum. So I started part-time and worked with visitors on a daily basis, and now I get to run some of the programs here at the museum, educational-wise.

The Unknown Science Behind Civil War Era Medicine

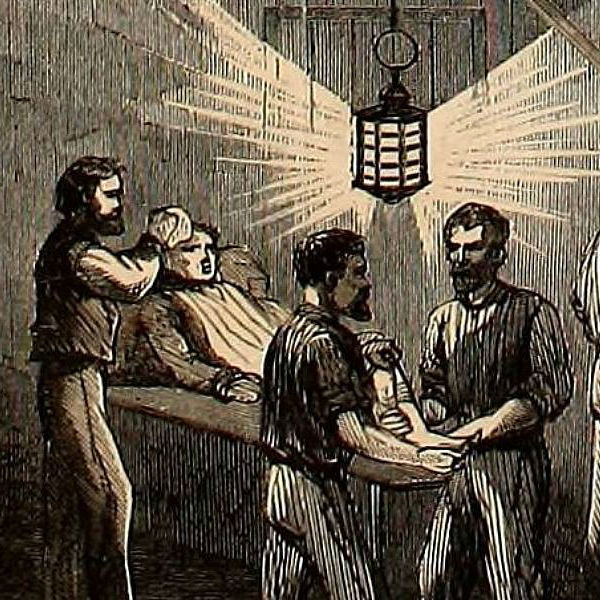

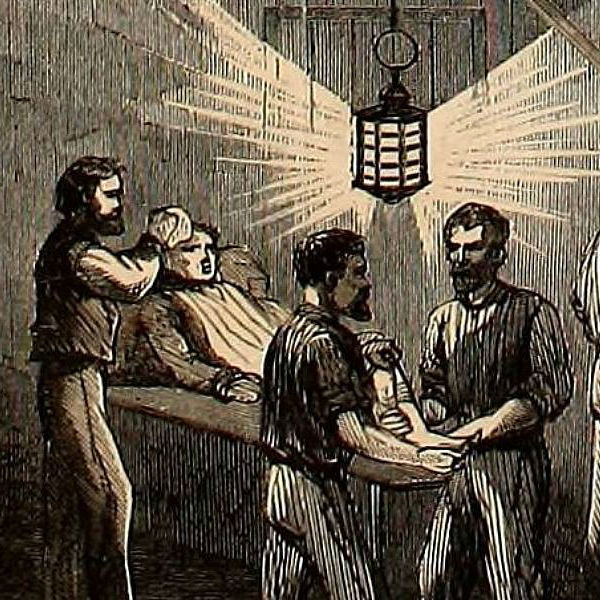

[NR] So the museum, for those listeners who aren’t familiar with it, is based in Frederick, Maryland, downtown Frederick, Maryland. And it tells the story not just of Frederick, of course, but the much broader story of medicine in the Civil War, which is large sort of mythologized, I guess and– there’s a lot of misconceptions about Civil War medicine. I think people think of just hacking off limbs indiscriminately without really any care, or reason, or any science involved. And obviously, you guys do a lot of work to refute some of those myths and legends about practices in medicine during the Civil War. What else would you tell people? I mean, what else are we missing? What else does the medical museum do?

[JW] You know, we really tell stories that– elements of the Civil War that most people don’t have a real deep knowledge and understanding of. So one of the struggles that we have here at the museum is in telling is the fact that people have a very instantaneous reaction when you say Civil War medicine. They have an idea in their head, like you said, hacking limbs, maybe biting a bullet during surgery because they didn’t have anesthesia and so initially we have to deal with that and that knowledge. But it’s also an opportunity to tell the true story of Civil War medicine, which is one of healing, is one of a rapid increase in knowledge and infrastructure in healthcare in America. And so it’s a great chance to take somebody’s understanding of the myth of Civil War medicine and transitioning that to giving them something to know about the Civil War that they had very little understanding of prior to visiting the museums.

[NR] Some museums are sort of trying to introduce people to a story, and obviously you’re doing some of that. But also, in a sense, you’re kind of a museum that is sort of trying to correct a story as well, which is interesting. People have this really wrong idea about what something was all about. And so you’re doing a lot of sort of catch-up work to try to bring people up to speed on the reality of it. That’s an interesting place to be and I think a place that is different than a lot of other museums. Does that strike you that way?

[JW] Yeah, and I don’t like to think of it as righting a wrong, even though it may sound like that. Really what we’re doing is building upon people’s knowledge of the Civil War. Many Americans know at least some small piece of American history from the Civil War era. And what we’re doing is trying to take that knowledge and build upon it and give it another element that they may not have thought of previously. So what we do here really is taking a place like Antietam or Gettysburg where people have an idea that these massive battles with tens of thousands of wounded and killed… And we’re taking and telling the story of what happened afterwards where the armies move on but dealing with the suffering and dealing with all of those casualties, somebody has to do that. And so we’re telling the stories of those folks who are dealing with the aftermath of a really horrific, bloody conflict. And that’s unique, and people wanted to know more about that story.

[NR] I was a park ranger at Gettysburg, and I’m reminded of a quote of Walt Whitman who talked about how “the real war will never get in the books.” And to some extent, you’re trying to put the real war not only in the books but in a museum, which is important work. So speaking of that real war, what are some of the techniques of Civil War medicine that folks may not be aware of that maybe didn’t make it in the books?

[JW] I would have to say one of the biggest misconceptions about the Civil War and Civil War medicine relates to the use of anesthesia in the operating room. Most people that walk in the door – and including myself before I started working here and before I really started studying Civil War medicine – there is this Hollywood-esque, Hollywood-created thought about Civil War medicine. It’s that it’s very archaic. That these doctors didn’t know what they were doing. They’re unprofessional. They’re hacking off arms and legs left and right like butchers. And that there’s no anesthesia in the operating room, and soldiers are biting down on bullets or sticks or something in the operating room. In reality, these doctors were extremely professional, especially later in the war. They’re going to be considered some of the best surgeons in the world as a result of all the carnage that they experience on the battlefield and in the hospitals of the war. Many of the operations that they perform are very similar to the ones we do today. If you receive something like an amputation after a car crash or some kind of accident like that, the doctors are utilizing the same kinds of techniques, the same tools as well as they would have been using in the Civil War. It hasn’t changed all that much.

But the biggest misconception about the war is that the doctors didn’t have anesthesia. They did. They had anesthesia and used it in 95 percent of cases. And they recorded that fact. And so we have statistics that show that they used either chloroform or ether in the operating room in almost every surgery. They recognized, going back before the Civil War, in the years before the conflict broke out, that if you put these patients under – they’re not fully going to sleep in the way that we use anesthesia today. If you can render them, as they called it “insensible,” they would relax. There is a much lower likelihood of patients going into shock and dying on the operating table. And so as a result of this – amputations are what you’re going to see most frequently during the war – 75 percent of those patients that undergo operations including amputation on a Civil War battlefield, are going to survive. It’s pretty impressive considering that they don’t know about germ theory at that stage. They don’t know about cleaning their instruments. But the techniques they’re using and the anesthesia that they’re using both were extraordinarily modern and we can learn from that even today and look at the techniques that they did and bring it back to our own time period and recognize that it was the cutting edge of medicine in those years. And so it’s not archaic. It’s not butchery. It was science and it was medicine as best as those doctors could provide in those years.

[NR] Thanks for that, Jake. You really gave us a good idea of the kind of information that people can gain from visiting your Civil War Medical Museum. So let me ask you, with respect to digital content and technology, how has that worked at the medical museum? Have you guys begun to integrate that into the work that you do? What kind of success have you seen there?

[JW] Absolutely. Digital is where we put a lot of our focus on putting things up on our website, putting things online, on our social media channels. My boss, the Executive Director here at the museum David Price, he kind of has a motto which is “we want to get our museum 100 percent online.” We want people to be able to access our collections and our stories from anywhere on the globe. And that starts out with a blog and getting our collections online in a catalog form so people can search it and databases and these sorts of things that people can go on the Internet, go on to our website and check them out. And then social media acts in tandem with that on a day-to-day basis. Updating our visitors, updating people that are interested in Civil War medicine and just the general public in what we’re doing day by day by day and…telling the story and how that is changing our understanding both on a personal level and as an organization and you can look at it even as a wider historical community. Our understanding of these topics and Civil War medicine and the Civil War in general, is always changing and it’s always evolving.

[NR] So let me ask you, I mean, on that point particularly with respect to the social media side, I think a lot of people listening, particularly individuals who may represent a preservation group or maybe they work at a small museum themselves that are trying to begin to dabble in this, what would you say say is the– just sort of out of curiosity, what’s the most engaging type of post that you guys have found? What’s the thing that really drives interest on the social media side from you guys’ work?

[JW] What we have had the most success with is two kinds of posts. Links to our own content have been most successful for us, and this comes from really two directions. One from our blog which we’ve been updating and keeping it fresh with new content. But also polling from our back catalog of expert’s analysis and things that have been written for our journal, which we are getting that up and online, and that has been incredibly popular. People want to read that. And what we do, myself and Amelia Grabowski in our education department, we take that content that is relatively stable, and through social media, we relate it to the events of today. So if a certain topic comes up, something in regards to a disease outbreak or hunger in the Syrian Civil War. We can take the stable of content that we have and adapt it and utilize it and make it relevant to whatever conversation is going on on social media and in people’s lives.

[NR] So it’s interesting because I think you’ve hit on two big things in terms of the use of technology, and we’ve talked to some other organizations. We talked to the head of digital resources at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. And he hit on two very similar points. And we’re hearing this over and over again as far as how to engage people in archives of issues– preservation, history, museums. And that is: trying to remain relevant, connecting your story to something that’s happening in the world, while making sure that you don’t get political or get too far into it… but trying to tie your work to something relevant. But also this idea of using your existing catalog. That not everything has to be created out of whole cloth. You don’t have to go out and recreate all content, that most organizations already have a treasure trove of content that they can draw back on if they sort of think about it in new ways. So the big takeaway is that content is king, particularly native content that you guys are creating. So on that same theme of taking something old and repackaging it, do you have a story that’s told at the museum that you think is relatable to the present day that’s sort of been repackaged in that way?

[JW] Another really great question. Throughout the museum, we track the story of one particular soldier experience the Civil War. He was a really young man when he enlists, 21 years old. His name is Peleg Bradford. He came from the state of Maine, joined the Union army in the summer of 1862, goes off to war, and does not really experience the traditional Civil War soldier experience. He’s not really going out onto the battlefield at all for the first two years of his service. Instead, he sits around in forts protecting the nation’s capital, protecting Washington D.C. And he experiences illness. He’s battling against things like typhoid fever, things like measles, that are breaking out in these Civil War forts. And that’s the number one killer of soldiers during the Civil War, is going to be disease, not wounds on a battlefield. But Peleg does experience the battlefield in 1864. He’s involved in heavy fighting around the city at Petersburg, Virginia. And it’s there that he is shot through the leg and has a leg amputated. And so we see through his letters the experience of the kind of average soldier through the Civil War dealing with disease, dealing with this horrible wound that he experiences, the trauma of going through an amputation. And even more traumatic and really enlightening for us today is to read about the aftermath of that operation. Now he’s going to have to go home to Maine as an amputee, as a disabled former soldier. And the letters are really enlightening because you see him trying to struggle with, how does he tell his family? How does he tell his girlfriend back home in Maine that, “Well, I’m not coming home the man that I went off to war as? I’m not coming home as a whole person.” And so in this era that we’re living in now, in the aftermath of really 15 years of consistent war, whether in Iraq or Afghanistan, there’s a lot of veterans that have the same story of going through the trauma of these horrific injuries and surviving. And then how do you live? How do you make a living? How do you survive after the war is over? And people aren’t necessarily thinking about the Iraq War. They’re not thinking about that as everyday kind of experience like these soldiers are. And so it’s very much a parallel between the Civil War experience of disabled veterans and what we’re seeing today as a result of more recent conflicts.

[NR] Wow. That’s an important statement I think you just made there on the power and relevance of museums. Well, we’re going to take a quick break and when we return we’re going to talk a little bit about what you think might be the next step in integrating museums into the digital age. We’ll be right back here on Preserve Cast.

Maryland: Mini-America

[Stephen Israel] Yeah, you heard that right. There is Civil War medicine themed beer. There’s a lot more to history and beer than present day partnerships. The history of beer and breweries in Baltimore and Maryland at large, extends as far back as the mid-eighteenth century when German immigrants brought their craftsmanship to the then-colony. In 1748, John Leonard Barnitz established what may be considered the city’s first commercial brewery. He was, of course, followed by many German and European immigrants with names like Bauernschmidt, Veisner, and Eigenbrodt, which all continued to be local breweries for many years. Well into the eighteenth century, Marylanders enjoyed many local breweries, and the practice wasn’t limited to Baltimore.

In places as far as Cumberland there were as many as thirteen local breweries in the 1880s – some producing hundreds of barrels a year. Now, we’re talking about Maryland and beer. There is of course, the elephant in the room: National Bohemian. (Natty Boh, Boh’s and Oh’s.) The National Brewing Company started during the height of Baltimore brewing in the 1870s producing national premium beer. And in 1885 they rolled out the National Bohemian. The Natty Boh didn’t always have the run of the mill, if you will. The 1880s also saw the origins of Gunther Brewing Company which was once almost as well-known to Baltimore natives as Mr. Boh’s brew itself. And both companies were located in the modern neighborhood of Brewers Hill. It wasn’t until after the Prohibition Era that the National Bohemian and Gunther brands truly became a Baltimore phenomenon. The Mr. Boh mascot didn’t start confusing Marylanders with his single eye until 1936. That was also around the time that Gunther started using their once-famous marketing slogan, “Gunther’s got it.” That slogan was so well-known that if you ever wondered what happened to Mr. Boh’s missing eye, all you had to do was ask any child on the street and they’d be happy to tell you that Gunther got it. Over the next few decades, Marylanders fell in love with both brands. In the 1940s, the National Brewing Company became a trendsetter by rolling out the first six-pack as a unit of beer in the United States. And as recent as 1959, Gunther Brewing was one of the largest beer producers in the state. However, it was at that time that they were bought out by Hamm’s, a Midwestern brewery that chose not to keep the Gunther’s name and because of that lost a significant portion of their local customers. Soon after came the peak for National Bohemian in the late 1960s when the company’s president Jerold Hoffberger owned the Baltimore Orioles. Unfortunately, his popularity couldn’t stop the nationwide move to larger breweries and, after a series of mergers and buyouts, Natty Bohs are currently produced by Pabst Brewing Company. The last Maryland production facility in Halethorpe closed in 2000 but Natty Boh is still available across the state. In 2011, after a 15-year span of only being available in bottles and cans, Natty Boh is once again served on a tap straight from the keg. Today, brewing in Maryland appears to be moving closer to its roots, joining the national trend with local and regional craft brews becoming popular once again. Everybody has their favorites, but I think I might just have to stop talking about beer and let you guys get back to PreserveCast.

[NR] Do you have questions? We may have answers. If at any point during this podcast you’ve thought of a question that you have for us or maybe one of our guests, we’d love to hear about it. You can send an e-mail to podcast@presmd.org and we’ll try and answer it right here on the air, on the next episode of PreserveCast.

The Civil War and Modern-Day Beer

[NR] Hi, this Nick Redding. You’re back with PreserveCast and we’re talking with Jake Wynn, Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. And we were having the discussion about what has really worked, where the challenges have been. And challenges, like any nonprofit, of what we’re hearing with is sort of the bandwidth of doing all of this– that you only have a certain amount of folks dedicated to it, like every organization. And that’s only a sliver of their overall portfolio of work. But I have to say you guys do a really phenomenal job, which is one of the reasons we wanted to talk with you. We’re just curious– obviously no one has a crystal ball about how this is all going to work– but do you have any dreams or concepts of how a museum like yours could become even further integrated? Obviously, we’ve talked about releasing content and sharing information about partnerships but ten years down the road, what could you envision as someone who works in a museum as a way that you may be even more integrated into digital world?

[JW] That’s a really good question. I think that utilizing tools and we’re seeing those tools develop now, things like Facebook Live– things that are allowing instantaneous communication between a digital visitor and what’s going on in an organization at any given moment. And so that kind of development is really only just beginning. And we’re only just starting to utilize that here at this museum. What I think is going to happen [over the next ten years] is that there’s going to be more integration between digital and the real life, the tangible. And as we are struggling with that, all kinds of challenges come up from that. When we talk about getting our museum 100 percent online, there is a certain pushback against that because there’s always a fear of whether or not people are going to come and visit the museum. Now the way that we look at it is that we’re giving them a piece of the story. We are giving them a lot of information about either the collections or our events or any number of things that we’re doing here. But what we truly believe is that getting all of the information in beforehand means that they are going to come in here armed with all kinds of great information and we can foster new conversations. Because that’s ultimately what we want.

[NR] Right. You’re only ever going to be able to have a certain number of people actually physically visit your museum. And so being able to reach them in different ways. I think that the argument that you worry people won’t come – I think that if people are passionate about it, and you catch them and capture their interest, then actually, you have a better shot at getting them to come, so. And I’d be curious if the numbers bear that out, if your visitation over the years here now begins to trend upward as you become more dominant in social media and on digital side. That’ll be the real test of it I suppose.

[JW] Absolutely. And we really are only just at the beginning of this. When myself and Amelia Grabowski came online full-time here, one of the biggest focuses we put on ourselves – we were given kind of… folks here didn’t necessarily grasp the full abilities of social media to assist the museum’s mission. We really jumped on this opportunity to begin making a robust digital outreach to social media communities. And we have seen, anecdotally at this point, an increase in interest and people seem to be more passionate and come in armed with some really great information that we’ve helped foster more of an interest in them. And when they come in to us, we see that in the questions that they’re asking. We see that in all different sorts of ways. One of the things I love most about helping to manage social media is the metrics of it. The tracking all of this data that’s coming in. It gives us lots of information about how we can better do our jobs here. Not necessarily just online but also in person. What really resonates? What stories do people want? Do they want more relevance to what’s going on today or do they want more of a focus on what happened in the past and looking at it just as it’s in the past and not relating it as much.

[NR] Right. And that’s something we’ve done here, as well. Where it’s sort of, looking at where your constituents [are] asking questions or where do they need support. What are they asking for? And allowing that to drive the manner in which your organization works or the goals and priorities that it sets. So Jake, could you tell me a little bit more about the museum’s partnership with Flying Dog Brewery?

[JW] Yeah. This is a great partnership. Our organization really looks for community partners that can share some aspect of the Civil War medical story in kind of the new, interesting, diverse sort of way. And alcohol plays a huge role in Civil War medicine. You can see it in the hospital wards of the time. You see it on the battlefield. You see it pretty much anywhere there are Civil War soldiers, you see some sort of alcohol. And beer is really important to some of these doctors in these hospital wards. Because they’re using it both for sustenance and their also using it as part of their course of treatment for various diseases and in some cases, for certain wounds. Just one fascinating example to me is that there’s a hospital in the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia, called Chimborazo. It’s just west of Downtown Richmond. And they had a 400-keg brewery onsite at the hospital. So you see right there that beer is important for Civil War medicine. It’s being used all the time. And so we have identified local breweries. First, we used Brewer’s Alley, kind of a microbrewery here in Downtown Frederick, Maryland. And now we have stepped up to the next level with Flying Dog Brewery, which is a nationally and internationally recognized brewery. And so, we are now on our second beer with them called Dragon Lady. And that is inspired by Civil War nurse, Dorothea Dix, who got the unflattering nickname of “The Dragon” because she was so forceful in her belief that women should in the hospitals of the Civil War working as nurses. And so it gives us a really interesting way of talking about these stories that we talk about every day, but we get to go out and find a new audience. Typically a much younger audience than what we’re normally seeing through the museum or at our programs and so it gives us a new way of reaching out to the public in an interesting and fun sort of way.

[NR] Yeah, I’ve had that Saw Bones beer. That is really good.

[JW] Awesome. It’s a good one. We have so much fun working with Flying Dog. They’re a ton of fun working with and it’s really important to us to be able to go out and reach these new audiences, but also to share in kind of the camaraderie of just going to the brewery or going to a pub and talking about some of these stories. But mostly we’re out there, it gives us a new opportunity to make friends for the museum. You’re always going to have good will when it comes to serving historically-inspired beer, we’ve found.

[NR] Let me ask you this as we sort of draw to a conclusion. We normally ask simply what is the favorite historic building of the person that we’re talking to but since we’re talking to a bonafide Civil War– I mean, I’m a bonafide Civil War nerd so I’ll extend that to you as well. You’re a bonafide Civil War nerd. We’re going to ask two questions, which is what is your favorite historic building if you have one and perhaps what is your favorite event from Civil War history in Maryland?

[JW] Yeah. Really great questions and ones that I’m going to really enjoy answering. My favorite building I would have to say– we have such a great historic district here in downtown Frederick. It’s 40 or 50 blocks of historic neighborhoods and a historic downtown and there are a ton of great buildings in terms of architecture and history here and it’s really tough to choose but I think I do have a favorite one and that is the Evangelical Lutheran Church here in downtown Frederick. The city is known for its clustered spires from the Civil War time period and the Lutheran Church has these really great double spires. They’re tall. They’re some of the tallest buildings in Downtown Frederick. And there is a photograph taken inside that church in the fall of 1862, while it’s being used as a Civil War hospital for a short period of time. And you can see all of the patients, and you can see the doctors, and you can see the nurses and some civilians visiting. And you can see the way the building looked at that moment in which many of the other churches and buildings in Downtown Frederick that were also being used as hospitals, you don’t have that. You have the letters and diaries. You don’t have the photographic evidence. And so just from that point of view, you have an exact look that it had at that moment and you can get into that building in that historical sense. More because you can see it. You can see exactly where the beds were placed. You can see exactly where the doctors were standing, where they were storing their supplies. And that is just a really incredible building that is still here. I walk by it every day on my way to work. It’s a really incredible place. And representative of a much larger story here in Frederick as it’s being used for 8,000 patients after the battles of South Mountain and Antietam in September of 1862.

[NR] Wow. So when people talk about the power of place, maybe we should just use the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick as the poster child for that kind of thing, because that really kind of brings home that concept and really sharpens it in a really great way. You really described that wonderful. So let’s wrap up here with the favorite event in Maryland Civil War history. You have a lot to choose from, so I’m curious to see which way this goes.

[JW] Yeah, I really do have a lot to choose from, but I have one particular moment that’s really resonated with me for a long time and that is the Battle of South Mountain but specifically the Battle for Crampton’s Gap on September 14, 1862 –

[NR] Which took place, just for those listening, in Burkittsville, Maryland, where Preservation Maryland is working on a Six-To-Fix project at the Shafer Farm.

[JW] Yeah and that’s a really exciting project. But the reason that I got so interested in that particular part of that battlefield and part of the 1862 Maryland campaign is because I’m really interested in one particular unit from Pennsylvania. It’s where I grew up. It’s the 96th Pennsylvania Volunteers. And that is going to be…one of their first major engagements of the Civil War in a place where they’re going to suffer the most casualties on one day that they’re going to experience in four years at war. So I really honed in on their story and followed their footsteps and tried to visualize what they would have experienced as they suffer tremendous casualties in fighting their way up a very steep mountain path. And it’s also a story that in comparison to the absolute bloodbath that occurs three days later during the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of South Mountain is less understood even [by] Civil War buffs and it’s a story that really deserves…to get more airtime and to have the spotlight because the decisions made on September 14th really play into what takes place three days later in Sharpsburg.

[NR] Well, we couldn’t agree more particularly because we’re working on a project at Crampton’s Gap ourselves. So if people want to find out more about you and the Civil War Medical Museum, where should they go? Where would you direct them?

[JW] I would direct them two places: CivilWarMed.org is our website. We just revamped that within the last couple of months. There’s a lot of great stories there from our blog, from our journal, stories. And if you’re doing research it’s a great place to go because we have a database of all of the wounded soldiers that were treated here after the Battle of South Mountain in Antietam in September of 1862. So it’s a great resource. The other places I would suggest to go: you can follow us on Twitter @CivilWarMed, and Instagram @CivilWarMed, and National Museum of Civil War Medicine on Facebook, which is actually where we update most frequently with, like I said earlier, links to articles that are fascinating and you might not get anywhere else; photographs, where we analyze photos from the Civil War; and lots of other great content as well as conversations between us and our visitors both here in the museum and online.

[NR] And then if people want to find the Wynning History Blog, where do they find that?

[JW] Yep, you can go to WynningHistory.com. And that’s where you can find me writing mostly about Pennsylvania history, but you will find some stories about Maryland Civil War history as well.

[NR] And that’s W-Y-N-N-I-N-G, is that right?

[JW] That is correct.

[NR] A little bit of a play on words there with Jake Wynn. Well, Jake, thank you so much for joining us, and thank you for the work that you do. You tell a incredibly important story. I would implore everyone listening, if you’ve enjoyed this interview to make sure you take time out of your schedule and go and visit Jake and everyone else at the Civil War Medical Museum in Frederick. Thanks again, Jake. It has been great talking with you.

[JW] Thanks for having me.

Credits

You don’t need to open a history book to find us and available online from iTunes and their Google Play Store as well as our website: PresMD.org. This is PreserveCast.

This podcast was developed under a grant from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, a unit of the National Park Service. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Preservation Maryland and the Maryland Milestones Heritage Area and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Park Service or the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.

This week’s episode was produced and engineered by Ben and Stephen Israel. Our executive producer is Aaron Marcavitch. Our theme music is performed by the band Pretty Gritty. You can learn more about them at their website: PrettyGrittyMusic.com, on Facebook, or on Twitter @PG_PrettyGritty.

To learn about Preservation Maryland or this week’s guests, visit: PreservationMaryland.org. While there, you can check out our blog and learn about what’s current in historic preservation. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Flickr, and Twitter @PreservationMD. And of course, a very special thank you to our listeners. Keep preserving.

Show Notes

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland also operates the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office in Washington, DC and the Pry House Field Hospital Museum at Antietam National Battlefield.